In our twenty-first century urbanised world, buildings of enormous height and size are all around us and are so familiar a sight that we rarely pay them much attention. We are accustomed to living, working and shopping in them. When a new one is built, we see huge cranes and other heavy machinery employed, with elevators and lifts taking contractors up to where they need to be.

|

| Canterbury Cathedral © E.M. Powell |

Anybody time-travelling from the medieval world to now would be understandably astonished by what we can achieve. Yet the reverse is also true. We cannot of course travel back to medieval times. But we can stand next to a vast cathedral such as Canterbury and wonder how on earth it could be constructed by people who had only the most basic of tools.

There has been a cathedral in Canterbury for more than 1,400 years. Saint Augustine consecrated the first cathedral there not long after his arrival in the year 597. There is no trace of the original building, as a fire in 1067 destroyed it and it had to be completely rebuilt. Archbishop Lanfranc oversaw much of the construction, but it was his successor, Archbishop – and later Saint – Anselm, who built the ‘glorious quire’ –of which more later––and the enormous crypt.

The credit might be Anselm’s but his hands were not the ones that wielded axes, hammers and chisels, and mixed mortar that is still holding up the walls after almost a thousand years. Those people, with their remarkable skill and ingenuity, were the medieval stonemasons.

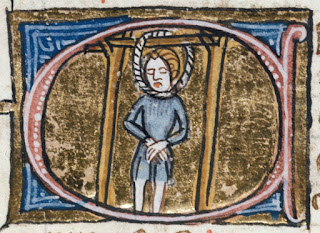

|

| Building- Canterbury or Anglo-Catalan Psalter 12th Century Public Domain- British Library |

The stonemasons’ guild, the Worshipful Company of Masons, is one of the ancient Livery Companies of the City of London. It was formed for the purpose of regulating the craft of stonemasonry and ensuring that standards could be properly maintained and rewarded. The earliest available records of regulation from the Court of Aldermen are from 1356.

The preceding two centuries had already seen massive growth in stone construction–royal, ecclesiastical and municipal–and alongside that came major developments in the skill of stone masonry. Stonemasons were by no means a homogenous group. Their skills ranged from the most basic to outstanding artistry, though categories of worker were fluid. Rates of pay varied from job to job too.

Before stone could be used as building material, it first had to be dug from the earth and that was the task of the quarrymen. The records use the term ‘quarrymen’ to refer to those who owned the quarries as well as those who worked in them. While the quarry owners were frequently men of means and high social standing, those who actually worked within the quarries were not. The work was back breaking, digging and breaking stone in poor conditions that led to health problems like silicosis, a lung disease induced by inhaling flinty or siliceous particles. The quarriers also partially or completely worked the stone before it was transported to its destination, as this saved on cost. In addition to providing the supply of stone, the quarries often served as schools where stoneworkers could learn the basics of the craft, before moving on to more skilled employment and better rates of pay.

|

| Canterbury Cathedral interior stonework © E.M. Powell |

Roughmasons and layers prepared wall stone with scappling hammers and might also hew stone with an axe into the approximate shape required. Fine carving was done with a mallet and chisel and this was the work of the freestone mason. The freestone mason did not simply step in and apply the last artistic flourishes. He would also have had to be an expert stone hewer and layer to ensure that intricate work fitted perfectly and robustly together. Building work was not solely the preserve of men either. The records show women working as masons’ servants and plasterers.

Overseeing any project was the master mason, frequently assisted by an undermaster or a second master mason. Master masons were not just the most skilled stone workers: they were architects, designers and visionaries as well as capable administrators. They had shared responsibility with the abbey or nobleman who had embarked on the construction project for the financial accounts. These covered every aspect of expenditure: wages, materials and transport. The master masons were involved in the hiring and dismissing of their workers.

|

| Mason and carpenter, Bruges, 15th Century Public Domain- British Library |

In general, masons were a highly mobile group. They travelled to where the biggest and best-paying jobs were, including from country to country. Quarrymen tended to live locally to their work.

In order for the best work to be produced, the most suitable materials had to be sourced. Huge quantities of wood went into building a structure like Canterbury Cathedral. But wood is much easier to source and transport than stone. And it could not be just any stone: it had to be soft and easy to carve. Canterbury’s cream limestone came from Caen in Normandy as it could be delivered by ship, rather than trying to move stone along medieval roads.

|

| Canterbury Cathedral Choir © E.M. Powell |

Such transport was not without risk. An account exists from the days of William I of a flotilla of fifteen ships that were sailing from Caen with cargoes of stone. Fourteen carried stone for the king’s new palace at Westminster and one was full of stone for Saint Augustine’s abbey in Canterbury. The ships foundered in a terrible storm and fourteen were lost. The one with the Canterbury stone was about to suffer the same fate. The master and crew prayed to Saint Augustine himself, bailed furiously and made it as far as the Sussex port of Bramber, where the ship split open and all the stone ended up on the sands. The master got hold of another ship, reloaded his cargo and delivered the stone to the abbey. A delighted abbot paid the master ‘a bonus of some shillings’. A relieved master offered half the money to God and Saint Augustine in thanks for his miraculous escape.

Speaking of saints and miracles, Canterbury Cathedral’s most famous archbishop is another saint: Thomas Becket, who was murdered there on 29 December 1170. He was slain by four knights acting on one of King Henry II’s legendary outburst of temper. The knights’ original intention may have been to arrest Becket, who had been engaged in a monumental power struggle with the King for several years. But the situation quickly deteriorated, and Becket was hacked to death on one of the altars. The Martyrdom is still maintained in the cathedral and one can stand at the very spot.

|

| Sculpture of the sword's point at the Martyrdom- site of Becket's murder in the cathedral. © E.M. Powell |

The miracles quickly began. Word quickly spread and the devotion to Becket the Martyr began, with his tomb becoming a major site for pilgrimage.

It was a huge stroke of good fortune that the monks had chosen to place Becket’s body in a stone tomb in the crypt while they set about constructing a shrine. For on 5 September 1174, fire broke out in three cottages near the cathedral. Unknown to everybody before it was too late, the blaze spread to the roof of the cathedral. A monk, Gervase of Canterbury, wrote a vivid account of the fire, with its black smoke and scorching flames. Consumed by flames, the roof collapsed into the choir and its wooden seats. The flames rose up ‘a full fifteen cubits, scorching and burning the walls’ and causing terrible damage to the stone pillars. Anselm’s choir was destroyed. Gervase describes the reaction of those who witnessed it. He talks of people overcome with ‘grief and perplexity’ blaspheming at such an event and unable to comprehend that it had happened.

|

| Notre Dame Fire Baidax, CC BY-SA 4.0 |

A modern reader might dismiss this as an overreaction. But on April 15 2019, fire broke out in the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and millions worldwide witnessed a medial cathedral burn in real time. People’s reactions on social media and on news reports were almost identical to those reported by Gervase eight centuries ago.

Back in twelfth century Canterbury, the monks were faced with the daunting task of reconstructing their fire-ravaged choir. They commissioned master mason William of Sens, known for his brilliance and technical expertise. Unfortunately for him and for future generations, William fell from faulty scaffolding in the choir in 1178. He was badly injured and never recovered. He was replaced and the work was finished by another mason, William the Englishman.

|

| Stone conservation work, Canterbury Cathedral © E.M. Powell |

The stonemasons of Canterbury Cathedral continue their work to this day, with a team of over two dozen. Their job is to conserve and to preserve the building. And they work with tools on blocks of stone brought in from a quarry near Caen- just as the masons of a millennium ago did.

~~~~~~~~~~~

References:

Foyle, Jonathan, Architecture of Canterbury Cathedral (London: Scala Publishers Ltd., 2013).

Gimpel, Jean, The Cathedral Builders (New York: Harper Colophon Press, 1983).

Guy, John Thomas Becket (London: Viking, 2012).

Keates, Jonathan and Hornak, Angelo, Canterbury Cathedral (London: Scala Publications Ltd., 1980).

Knoop, Douglas and Jones, G.P., The Mediaeval Mason: An Economic History of English Stone Building in the Later Middle Ages and Early Modern Times (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1933).

Urry, William, The Normans in Canterbury: Occasional Papers No.2 (Canterbury Archaeological Society, 1959)

Urry, William, Canterbury Under the Angevin Kings (University of London, The Athlone Press, 1967).

Woodman, Francis, The Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral (London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981).

Websites:

The Worshipful Company of Masons

Canterbury Cathedral- stonemasons

I wrote this post for the English Historical Fiction Authors blog where it was published on November 15, 2020.