King Henry II of England is best known in the popular imagination for the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket, a murder for which the King was blamed. Four knights broke into Canterbury Cathedral on 29 December 1170 and slew Becket in the most brutal manner.

Whatever one’s view of the volatile Henry, there is one achievement from his thirty-five-year reign that stands above all others: his reform of the English legal system, which laid the foundations of the English Common Law. When he came to the throne in 1154 at the age of just twenty-one, his realm was in deep disarray following civil war. He urgently needed to re-establish royal authority and impose order and set about doing so with his customary relentless drive. The judicial system was the subject of much of his attention and he was aided in this by the talented Becket, who was his chancellor at the time.

Henry addressed reform of both land law and criminal law. With land law, cases relating to an individual being dispossessed or those in which inheritance was in dispute were now settled in a trial by jury. The jury system was far quicker and more efficient than the system it replaced. Given that said system was one of trial by combat, one can see why it was not just the efficiency of the new system that made it so popular.

His reform of criminal law was even more impressive. He issued new legislation at Clarendon in 1166 and Northampton in 1176. It was at Clarendon where the procedures of criminal justice were first established, addressing how serious felonies such as murder, robbery and theft would be dealt with. Juries of presentment were established, consisting of twelve lawful men in each hundred (a subdivision of a county) and four in each vill (village). These juries were not there to decide on guilt or innocence, but to support an accusation of a serious crime.

Anyone who was accused of such crimes would be put in prison to await trial. Those trials could only be heard by the King’s justices, who travelled the country to do so. Henry first introduced his system of itinerant justices at Clarendon but refined the system at Northampton. England was divided into six circuits, with three justices, the justices of the general eyre, allocated to each. Twelfth century chronicler Roger of Howden lists the eighteen justices itinerant and their circuits for 1176.

One of the justices listed was Ranulf de Glanville. De Glanville was one of Henry’s staunchest allies, securing key victories for the King in the rebellion of 1173-74 and rising to the position of Justiciar of England. The ‘Treatise on the Laws and Customs of the Kingdom of England’, produced in the late twelfth century, is the earliest treatise on English law and is commonly referred to as ‘Glanvill’, though it is unlikely that de Glanville was its author.

The justices provided a system of criminal investigation for the whole country. The impact of the arrival of the travelling court should not be underestimated. It could consist of several hundred people, all of whom were tasked with supporting the royal justices in administering the law in the name of the lord King. As well as being administratively impressive, it would have been a spectacle that reinforced Henry’s power over all his subjects. It would also have instilled awe and fear in all those who witnessed it, especially those who were accused of a serious crime.

The accused were brought before the justices. Proof of their guilt or innocence could be established in a number of ways, such as witness testimony, documents or the swearing of oaths. Unlike criminal trials today, the jury acted as witnesses and not an impartial panel. They would give the account of what had happened.

In cases that were not clear cut or in those of secret homicide where there were no witnesses, the justices used the ordeal. Ordeal could be by cold water or by hot iron. The blessing of the water and the iron served to bring the notion of God’s judgement, judicium Dei, into the proceedings.

There was great ceremony and a long build-up attached to the ordeal, which would have added to the pressure on the accused to confess. The accused would be taken to church four days before the day on which the ordeal was due to take place. They had to wear the clothes of the penitent, fast and hear several masses. If they still did not confess, the ordeal would take place.

The most innocent of hearts must have quailed. Stripped to only a loin cloth, the accused would be led to the pit, which was twenty feet wide and twelve feet deep and full of water. A priest would then bless the water. God would now be the judge: His blessed water would receive the accused if innocent, reject him if he was guilty. The accused would be bound, thumbs to toes, and lowered in from a platform.

With ordeal by hot iron, the accused had to undergo the same preparation of fasting and penitence. A length of iron would be blessed and heated in a fire until it was red hot. The accused would have to take it in one hand and carry it for three paces. The injured hand would be bandaged and then examined three days after the ordeal. If it had healed, then innocence was proclaimed. If it had not, then the accused was guilty.

Both forms of ordeal were terrifying and horrific in themselves, and the lengthy preparations would have only added to the pressure to make a confession. Once the accused made a confession, it could not be retracted. In 1215, the Church forbade priests to take part in the ordeal, bringing an end to its use.

For those found guilty, the King’s punishment awaited. Hanging was reserved for the worst crimes. Thieves and robbers could lose a foot and, from 1176, their right hand. The law also had a final judgement it could impose, even if the accused was acquitted by undergoing the ordeal. If it was judged that the accused had a particularly bad reputation, as sworn to by the jury, then the accused was to leave the King’s lands as an outlaw and had to swear under oath that they would never return.

And lest anyone think that they could take the law into their own hands and administer punishments themselves, the King’s justices had a clear system of heavy fines for those who would dare to do so. Order would prevail. Henry, the consummate administrator, had thought of everything.

References:

All images are in the Public Domain and are part of the British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Bartlett, Robert, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal (Oxford, 1986)

Bartlett, Robert, The New Oxford History of England: England under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225 (Oxford, 2003)

Hudson, John, The Formation of the English Common Law (London, 1996)

Pollock, Frederick, and Maitland, Frederic William, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (Cambridge, 1898)

Warren, W. L., Henry II (Yale, 2000)

~~~~~~~~~~

I wrote this post for the English Historical Fiction Authors blog where it was published on October 3, 2018.

|

| The Murder of Thomas Becket c 1480 Public Domain- British Library |

Whatever one’s view of the volatile Henry, there is one achievement from his thirty-five-year reign that stands above all others: his reform of the English legal system, which laid the foundations of the English Common Law. When he came to the throne in 1154 at the age of just twenty-one, his realm was in deep disarray following civil war. He urgently needed to re-establish royal authority and impose order and set about doing so with his customary relentless drive. The judicial system was the subject of much of his attention and he was aided in this by the talented Becket, who was his chancellor at the time.

|

| Henry II enthroned, arguing with Thomas Becket c. 1307 - c. 1327 Public Domain- British Library |

Henry addressed reform of both land law and criminal law. With land law, cases relating to an individual being dispossessed or those in which inheritance was in dispute were now settled in a trial by jury. The jury system was far quicker and more efficient than the system it replaced. Given that said system was one of trial by combat, one can see why it was not just the efficiency of the new system that made it so popular.

His reform of criminal law was even more impressive. He issued new legislation at Clarendon in 1166 and Northampton in 1176. It was at Clarendon where the procedures of criminal justice were first established, addressing how serious felonies such as murder, robbery and theft would be dealt with. Juries of presentment were established, consisting of twelve lawful men in each hundred (a subdivision of a county) and four in each vill (village). These juries were not there to decide on guilt or innocence, but to support an accusation of a serious crime.

|

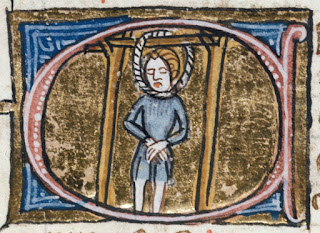

| Detail of an historiated initial 'I'(udex) of a judge c. 1360- c. 1375 Public Domain - British Library |

One of the justices listed was Ranulf de Glanville. De Glanville was one of Henry’s staunchest allies, securing key victories for the King in the rebellion of 1173-74 and rising to the position of Justiciar of England. The ‘Treatise on the Laws and Customs of the Kingdom of England’, produced in the late twelfth century, is the earliest treatise on English law and is commonly referred to as ‘Glanvill’, though it is unlikely that de Glanville was its author.

The justices provided a system of criminal investigation for the whole country. The impact of the arrival of the travelling court should not be underestimated. It could consist of several hundred people, all of whom were tasked with supporting the royal justices in administering the law in the name of the lord King. As well as being administratively impressive, it would have been a spectacle that reinforced Henry’s power over all his subjects. It would also have instilled awe and fear in all those who witnessed it, especially those who were accused of a serious crime.

The accused were brought before the justices. Proof of their guilt or innocence could be established in a number of ways, such as witness testimony, documents or the swearing of oaths. Unlike criminal trials today, the jury acted as witnesses and not an impartial panel. They would give the account of what had happened.

|

| Five judges and three plaintiffs c. 1360- c. 1375 Public Domain - British Library |

In cases that were not clear cut or in those of secret homicide where there were no witnesses, the justices used the ordeal. Ordeal could be by cold water or by hot iron. The blessing of the water and the iron served to bring the notion of God’s judgement, judicium Dei, into the proceedings.

There was great ceremony and a long build-up attached to the ordeal, which would have added to the pressure on the accused to confess. The accused would be taken to church four days before the day on which the ordeal was due to take place. They had to wear the clothes of the penitent, fast and hear several masses. If they still did not confess, the ordeal would take place.

|

| Two judges addressing a prisoner held by a court officer c. 1360-c. 1375 Public Domain - British Library |

The most innocent of hearts must have quailed. Stripped to only a loin cloth, the accused would be led to the pit, which was twenty feet wide and twelve feet deep and full of water. A priest would then bless the water. God would now be the judge: His blessed water would receive the accused if innocent, reject him if he was guilty. The accused would be bound, thumbs to toes, and lowered in from a platform.

With ordeal by hot iron, the accused had to undergo the same preparation of fasting and penitence. A length of iron would be blessed and heated in a fire until it was red hot. The accused would have to take it in one hand and carry it for three paces. The injured hand would be bandaged and then examined three days after the ordeal. If it had healed, then innocence was proclaimed. If it had not, then the accused was guilty.

Both forms of ordeal were terrifying and horrific in themselves, and the lengthy preparations would have only added to the pressure to make a confession. Once the accused made a confession, it could not be retracted. In 1215, the Church forbade priests to take part in the ordeal, bringing an end to its use.

|

| A man hanging from gallows c. 1360-c. 1375 Public Domain - British Library |

For those found guilty, the King’s punishment awaited. Hanging was reserved for the worst crimes. Thieves and robbers could lose a foot and, from 1176, their right hand. The law also had a final judgement it could impose, even if the accused was acquitted by undergoing the ordeal. If it was judged that the accused had a particularly bad reputation, as sworn to by the jury, then the accused was to leave the King’s lands as an outlaw and had to swear under oath that they would never return.

And lest anyone think that they could take the law into their own hands and administer punishments themselves, the King’s justices had a clear system of heavy fines for those who would dare to do so. Order would prevail. Henry, the consummate administrator, had thought of everything.

References:

All images are in the Public Domain and are part of the British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Bartlett, Robert, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal (Oxford, 1986)

Bartlett, Robert, The New Oxford History of England: England under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225 (Oxford, 2003)

Hudson, John, The Formation of the English Common Law (London, 1996)

Pollock, Frederick, and Maitland, Frederic William, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (Cambridge, 1898)

Warren, W. L., Henry II (Yale, 2000)

~~~~~~~~~~

I wrote this post for the English Historical Fiction Authors blog where it was published on October 3, 2018.