|

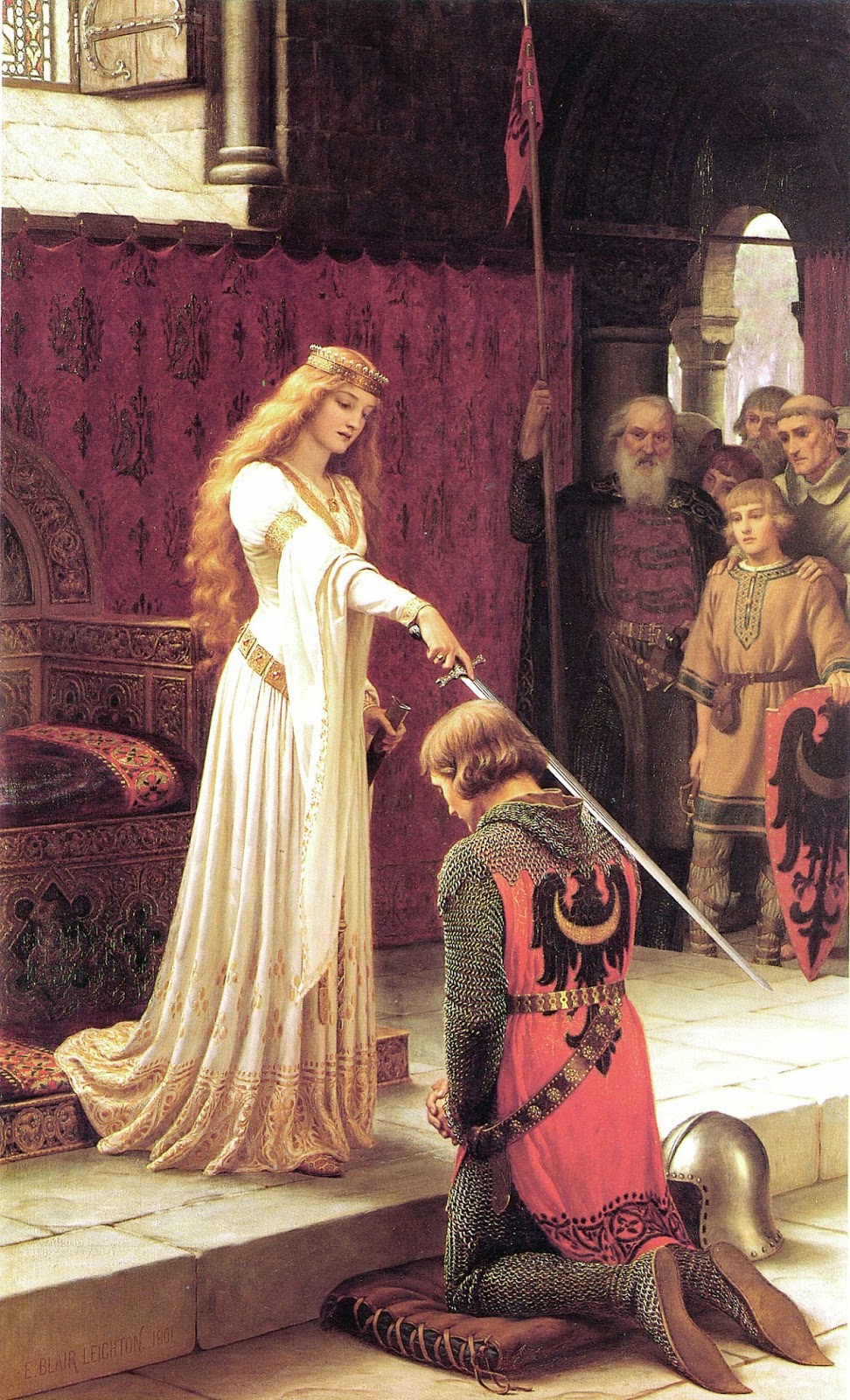

| The Accolade Edmund Blair Leighton, 1901 Public Domain |

It is frustrating that we know very little of Chrétien’s life. He was writing between 1160 and 1172, and it is suggested that he had a position as herald-at-arms at the court of his patroness in the city of Troyes. His patroness was the Countess Marie de Champagne, daughter of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Familiar to us all will be the notion of Courtly Love: this was also a concept running through Chrétien’s work.

Marie played a major part in taking this romantic ideal and promoting it as fashionable behaviour. Devotion and courtesy featured, but so did adulterous love. It should be remembered that adultery was considered amongst the gravest of sins by the medieval church. But Marie’s influence, and perhaps that of her mother, created a surge of interest amongst European aristocracy. (One commentator describes her as ‘this celebrated feudal dame’, a description which, to my eternal regret, conjured up a medieval Mae West on first reading.)

|

| The End of the Song Edmund Blair Leighton, 1902 Public Domain |

Chrétien wrote in Old French, rather than Latin. He composed at least five romances and two lyric poems. The word ‘romance’ also comes to us from this period. The Old French word romanz was first used in a literary sense to distinguish words written in vernacular French (romanz) from those in Latin.

So how did Chrétien happen on tales of King Arthur for inspiration? It would seem that Chrétien, like all good writers of historical fiction, liked a bit of a borrow from the past. Irish, Welsh and Breton legends have some mentions. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae, written in 1137, introduced the Arthurian legend to continental Europe. This was a Latin history written in prose. Anglo-Norman poet Wace produced Roman de Brut in 1155, a version of the history now in French couplets.

|

| King Arthur & the Knights of the Round Table Michael Gantelet, 1472 Public Domain |

Wace’s King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table (Wace’s is the first known mention of the Round Table; Chrétien has that for Camelot) were undoubtedly a more refined bunch than those written of previously. But they were still a group of fighters, rather than lovers. If his version were a historical novel, it would have swords and sandals on the cover, no question. It would take Chrétien to bring on the cover with the headless lady in the big dress.

In Chrétien’s romances we have knights riding out on adventures, fighting bravely against other warriors, monsters and magical creatures. And of course, the knights are also in pursuit of the love of their fair lady, often a love they lose, only to fight to get it back again. This latter storyline might be familiar to readers of the contemporary romance genre. But forget stereotypical images of swooning ladies. Chrétien doesn’t hold with damsels in distress. His ladies can be just as courageous and daring as his knights. When one considers the powerful woman that was one of Chrétien’s patrons, along with other powerful female patrons, this is hardly surprising.

|

| God Speed! Edmund Blair Leighton, 1900 Public Domain |

So what of the romances? First is Erec et Enide, with its straightforward tale of love, estrangement and reconciliation on an adventure-filled journey. It is set in Brittany and depicts King Arthur sitting on a throne emblazoned with a leopard. Such court scenes may have been inspired by Henry II’s Christmas 1169 court at Nantes in Brittany.

Second is Cligès, which is written against the background of the Tristan and Iseut story. It is an adulterous tale in which Cligès falls in love with Fenice, his uncle’s wife. She feigns her death with a magic potion, so they can be together.

Third up is Lancelot, or The Knight with the Cart. By far the most famous romance of Chrétien’s, it is the first tale of the adulterous love between Lancelot and Queen Guinevere. Though she is cruel to him, he obeys her every command and wish. Readers may not be familiar with its name, The Knight with the Cart. It is so called because in his search for Guinevere, Lancelot rides in a cart meant for convicted criminals. He is concerned for his honour (albeit briefly), but she is very displeased that he would hesitate in his search for her.

|

| The Parting of Sir Lancelot & Guinevere, 1874 Julie Margaret Cameron Public Domain |

Fourth is Perceval, a very lengthy yet not completed tale. Again, it introduces a story which has inspired so many, many more tales of searches and quests: the quest for the Grail.

Last, but by no means least, we have Yvain, or The Knight with the Lion. It is a spectacular romance and adventure, with a lion, a giant, a magic fountain and the widow who falls in love with Yvain, her husband’s killer.

|

| In Time of Peril Edmund Blair Leighton, 1903 Public Domain |

Lancelot and Guinevere. The Grail. King Arthur. Camelot. Chivalrous knights. All part of the popular cultural imagination, thanks to Chrétien de Troyes. We may not know much about him. But my goodness: we know about his stories. We are still retelling them today.

References:

De Troyes, Chretien: Arthurian Romances, Penguin Classics (1991)

Encyclopaedia Brittanica: Chrétien de Troyes

Jones, Terry & Eriera, Alan: Medieval Lives, BBC Books (2004)

Lindahl, C., McNamara, J & Lindow, J. (eds.): Medieval Folklore, Oxford University Press (2002)

Norton Anthology of English Literature: Chrétien de Troyes: www.norton.com

Weir, Alison: Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God, Queen of England, Vintage Books (2007)

Note: I originally posted this article on English Historical Fiction Authors on February 1st 2015.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

No comments:

Post a Comment